So we’ve seen that information from the world comes in through the sensory organs, which transduce (or translate) that information from its original form of energy (light energy, mechanical energy in the form of sound waves; chemical energy that is the basis of smells and tastes) into electrical energy in the form of action potentials. That’s necessary because electrical energy is the only form of energy that the brain can understand.

But there’s more sensory input coming from the environment than the brain can handle, so the process of selective attention pares things back in such a way that what arrives in the brain is a manageable amount of information.

I mentioned at the outset that when these action potentials arrive at the brain, the process of perception can begin – this is where the process of ‘seeing’, ‘hearing’, ‘tasting’ and so on actually starts. There are different regions of the brain that prioritize information coming in from the individual transducers (e.g., the visual cortex; the auditory cortex), but it's important to note that your perceptions are actually the result of many brain areas working together. This makes sense when you consider that you don't have sensory impressions of the world in isolation - instead, the information from all of your senses is combined in a process called multimodal integration (the word 'modal' comes from the fact that your senses are sometimes referred to as 'modalities').

And perception is amazingly quick and effortless – it’s S1 operating at its finest most of the time, creating a seamless experience for you that is usually accurate and happens unbelievably fast. If we go back to the metaphor of Achilles, then the process of perception is usually a good example of humans’ great strength. This section on perception is broadly divided into two pieces. The first looks at individual differences in perception; that is, why we see both similarities and differences in the way people perceive things in the world. The second piece examines two key processes that underlie the process of perception.

But there’s more sensory input coming from the environment than the brain can handle, so the process of selective attention pares things back in such a way that what arrives in the brain is a manageable amount of information.

I mentioned at the outset that when these action potentials arrive at the brain, the process of perception can begin – this is where the process of ‘seeing’, ‘hearing’, ‘tasting’ and so on actually starts. There are different regions of the brain that prioritize information coming in from the individual transducers (e.g., the visual cortex; the auditory cortex), but it's important to note that your perceptions are actually the result of many brain areas working together. This makes sense when you consider that you don't have sensory impressions of the world in isolation - instead, the information from all of your senses is combined in a process called multimodal integration (the word 'modal' comes from the fact that your senses are sometimes referred to as 'modalities').

And perception is amazingly quick and effortless – it’s S1 operating at its finest most of the time, creating a seamless experience for you that is usually accurate and happens unbelievably fast. If we go back to the metaphor of Achilles, then the process of perception is usually a good example of humans’ great strength. This section on perception is broadly divided into two pieces. The first looks at individual differences in perception; that is, why we see both similarities and differences in the way people perceive things in the world. The second piece examines two key processes that underlie the process of perception.

individual differences in perception

It won’t surprise you to know that there’s some variation in people’s perceptual experiences – when lots of people are confronted with the same scene, or the same sound, or the same smell, for example, some people’s perception of that stimulus or event will be the same, or similar, while other people will perceive that same stimulus quite differently. Psychologists refer to these as individual differences in perception (Don't be misled by the word 'differences'. When we talk about individual differences, we're referring to the fact that humans show variation, with some people being the same or very similar, and others being very different).

Sidenote: You'll hear a lot about individual differences in this course, because humans vary in lots of ways aside from their perceptions. For example, there are individual differences in personality, prejudiced behaviours, mental health, emotionality, sexual orientation and memory, just to name a few. Recall from Unit 1 that when they do research, psychological scientists are often trying to measure individual differences on variables that they care about and relate them to other individual differences (e.g., how differences in age are associated with differences in memory; how differences in depression are associated with differences in suicidal thinking; how differences in perception are associated with differences in driving skill).

In this part of the unit, I want to take apart three factors that help to account for these individual differences in perceptions:

Atypical Transduction

Let’s start with the sensory organs, and how they contribute to similarities and differences in perception.

I spoke earlier about the role of the sensory organs as transducers, or translators, and in the textbook you'll read more about how the process of transduction happens in each one (see Sections 4.3-4.6). It’s not a big mental stretch to understand that similarities in perception occur when those transduction processes operate the same way. So for example, people who have 20/20 vision and can see in colour will probably have more-or-less the same perceptual experience when they’re exposed to the same visual scene. But their perceptual experience will be different from other people whose ability to transduce light is known to be impaired in some way, maybe because they’re colour blind, or they have cataracts, or simply because they would need their glasses or contact lenses before they could see the scene properly. Similarly, if we pull together people whose hearing is designated as being in the normal range, they will probably have similar auditory perceptions to one another. But their experience will differ from people whose transducers for sound don’t function in the usual way because they are partially deaf.

Sidenote: You'll hear a lot about individual differences in this course, because humans vary in lots of ways aside from their perceptions. For example, there are individual differences in personality, prejudiced behaviours, mental health, emotionality, sexual orientation and memory, just to name a few. Recall from Unit 1 that when they do research, psychological scientists are often trying to measure individual differences on variables that they care about and relate them to other individual differences (e.g., how differences in age are associated with differences in memory; how differences in depression are associated with differences in suicidal thinking; how differences in perception are associated with differences in driving skill).

In this part of the unit, I want to take apart three factors that help to account for these individual differences in perceptions:

- atypical transduction, owing to the way that the sensory organs work

- the life experiences you’ve had

- the unique features of the situation

Atypical Transduction

Let’s start with the sensory organs, and how they contribute to similarities and differences in perception.

I spoke earlier about the role of the sensory organs as transducers, or translators, and in the textbook you'll read more about how the process of transduction happens in each one (see Sections 4.3-4.6). It’s not a big mental stretch to understand that similarities in perception occur when those transduction processes operate the same way. So for example, people who have 20/20 vision and can see in colour will probably have more-or-less the same perceptual experience when they’re exposed to the same visual scene. But their perceptual experience will be different from other people whose ability to transduce light is known to be impaired in some way, maybe because they’re colour blind, or they have cataracts, or simply because they would need their glasses or contact lenses before they could see the scene properly. Similarly, if we pull together people whose hearing is designated as being in the normal range, they will probably have similar auditory perceptions to one another. But their experience will differ from people whose transducers for sound don’t function in the usual way because they are partially deaf.

|

There are at least three reasons why transducers in the sensory organs may not work as they should, creating a sensory experience that is different from what’s typical.

One is genetic – the genes responsible for the development of those transducers may be faulty. Casey Harris of the X-Ambassadors, for example, was born blind. Derrick Coleman, the first deaf person to play in the NFL, was born with a genetic abnormality that caused him to lose his hearing by the age of three. |

|

A second reason that sensory organs may not function in a typical way has to do with aging. We know that transducers often don’t work as well in older adults as they do in younger people. Judi Dench, for example, has macular degeneration – a disease that impacts vision and is associated with aging. Similarly, age-related changes in hearing can, to some extent, explain the social media debate a few years ago about an audio recording that some people heard as “Laurel” and others heard as “Yanny”. Specifically, age-related change is one factor that can impact our ability to hear high-frequency sounds. In the original recording (which admittedly was not of good quality), hearing “Yanny” relies heavily on our ability to perceive those higher frequencies. And though age-related change is not the only factor that influences high-frequency sound perception, it offers one potential reason why older people might be more likely to hear “Laurel” than “Yanny". (If you have an interest in this phenomenon then see the video below, which shows you how perception can change when you remove the low and high frequencies). |

|

A third and final reason that explains differences in transducers' functioning is exposure to particular conditions or events in the environment. In some cases, people are exposed to things that damage the transducers or compromise their functioning in some way, which consequently distorts the sensory information that is sent to the brain.

Occasionally these effects are temporary; for example, earlier this year I had a bad viral infection that blocked up my right ear for the better part of 8 weeks and distorted my hearing. People with bad colds also sometimes report that they cannot smell or taste properly. However, sometimes the sensory organs are damaged in ways that lead to permanent changes in their ability to transduce energy. Halle Berry is mostly deaf in one ear, for example, as a result of blows to the head during an abusive relationship, and many other people experience deafness because of repeated exposure to loud noises (e.g., working with loud equipment, or ongoing exposure to loud music through earphones). |

Of course, vision and hearing are not the only senses that can be influenced by genetics, age, and experience - each of them can also impact smell, taste, and touch, as well as the kinesthetic and vestibular senses.

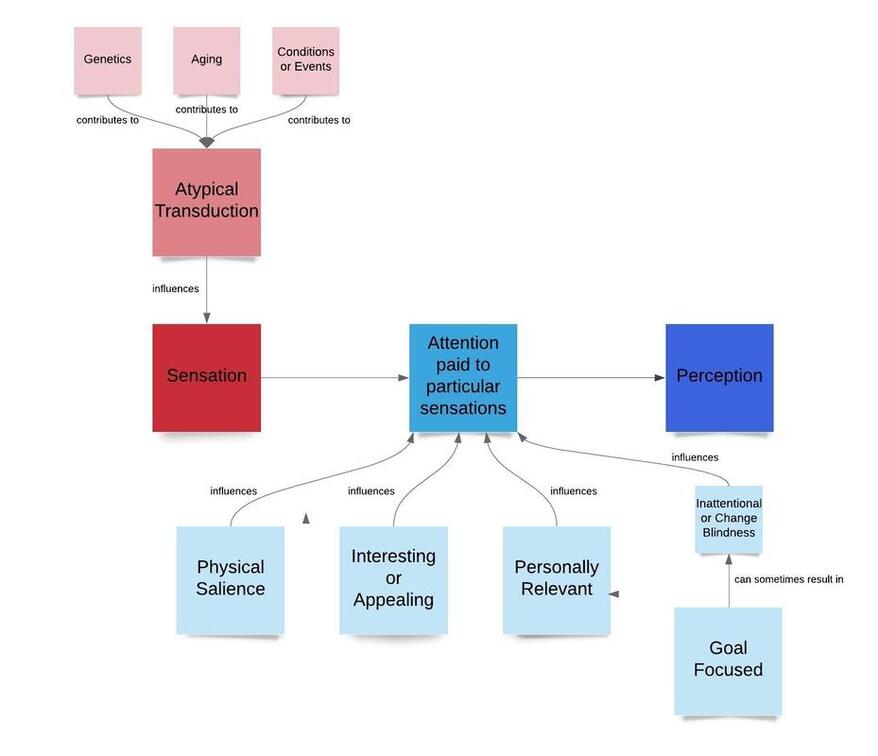

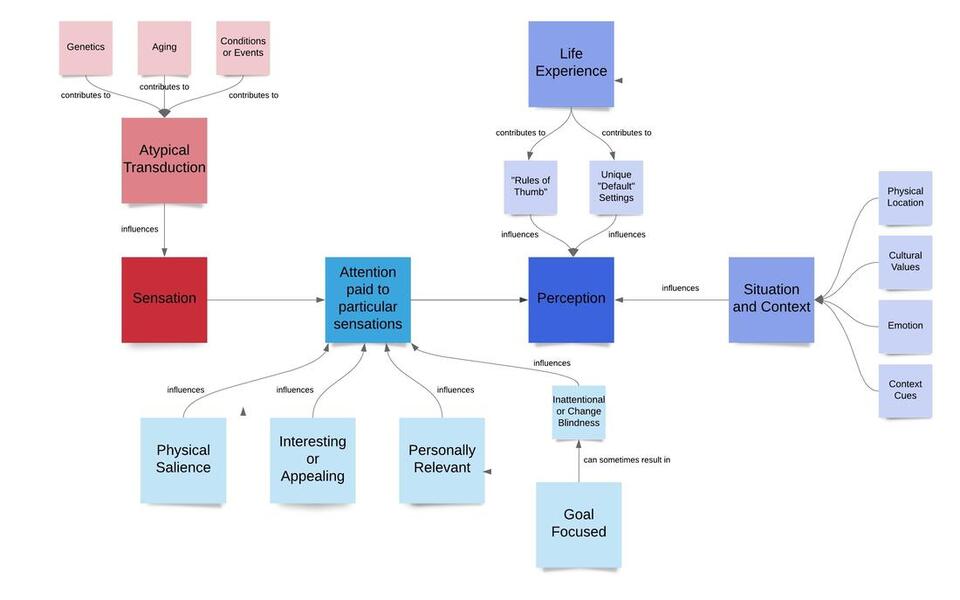

So far, then, the concept map looks like this:

The Role of Life Experiences

Life experience can also create similarities and differences in people's perceptions of the world. Take a look at this video to get a sense of some of the ways that experience can be important to our perceptions. Life experience is relevant to the perception of the illusions and depth (you can read about them later in Sections 4.7 and 4.8). It's also relevant to perceptual learning, described in Section 4.9.

Life experience can also create similarities and differences in people's perceptions of the world. Take a look at this video to get a sense of some of the ways that experience can be important to our perceptions. Life experience is relevant to the perception of the illusions and depth (you can read about them later in Sections 4.7 and 4.8). It's also relevant to perceptual learning, described in Section 4.9.

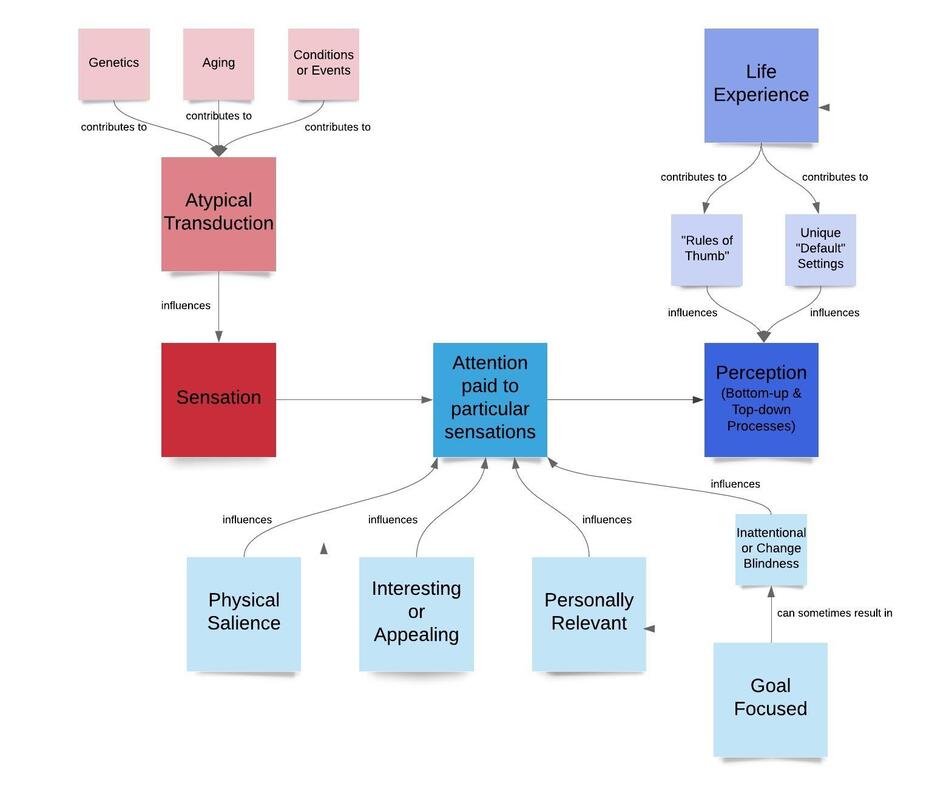

Filling out the concept map a bit more, we arrive at:

The Role of Situation/Context

We've talked now about how sensory organs and experience can promote individual differences in perception. Now, we'll take a look at how situational factors (or context) can also play a role in determining whether our perceptual experience is the same or different from others. We'll talk about four things that fall into this category, including physical location (not discussed in the text), as well as culture, emotion, and context (each of which is discussed in Section 4.9).

Let's start by taking a look at this video by Brusspup (who was also responsible for the clip of the chess board in my last video).

We've talked now about how sensory organs and experience can promote individual differences in perception. Now, we'll take a look at how situational factors (or context) can also play a role in determining whether our perceptual experience is the same or different from others. We'll talk about four things that fall into this category, including physical location (not discussed in the text), as well as culture, emotion, and context (each of which is discussed in Section 4.9).

Let's start by taking a look at this video by Brusspup (who was also responsible for the clip of the chess board in my last video).

Brusspup's video is all about anamorphic illusions, and demonstrate how perception is shaped by one specific situational variable - our physical location. People standing in different places relative to the stimuli (the Rubik's cube, tape, and shoe) will have different perceptions of them. Physical location also plays a role in the extent to which our perceptions based on hearing and smell are similar or different to others.

When it comes to situational factors that contribute to similarities and differences in perception, physical location is pretty obvious. But there are a host of other factors that also impact perception, usually through their influence on attentional processes.

For example, we know that cultural values can impact perception by influencing our attention to particular features of the environment, and influencing our interpretation of them (see Section 4.9).

In addition, emotions that you are feeling at any given moment can be important to perception. When we are in a positive mood, attention tends to be more expansive; in contrast, negative moods tend to narrow our focus (see Section 4.9).

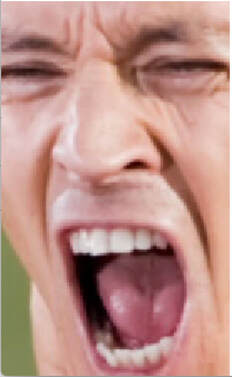

One final factor that I'll mention here is the importance of context. S1 is an expert on examining the environment in an effort to improve perceptual accuracy. Here's a good example: In a study, people who looked at the photo on the left and asked about the emotion being expressed were most likely to say either anger or pain. As the photo on the right makes clear, however, when there's some context around that stimulus the perception becomes entirely different.

For example, we know that cultural values can impact perception by influencing our attention to particular features of the environment, and influencing our interpretation of them (see Section 4.9).

In addition, emotions that you are feeling at any given moment can be important to perception. When we are in a positive mood, attention tends to be more expansive; in contrast, negative moods tend to narrow our focus (see Section 4.9).

One final factor that I'll mention here is the importance of context. S1 is an expert on examining the environment in an effort to improve perceptual accuracy. Here's a good example: In a study, people who looked at the photo on the left and asked about the emotion being expressed were most likely to say either anger or pain. As the photo on the right makes clear, however, when there's some context around that stimulus the perception becomes entirely different.

Here are a couple of other examples of how people use context cues during perception. Clearly, the middle character is exactly the same in both cases, but you'll perceive it differently depending on the context (that is the surrounding characters) in which you see it.

key processes in perception: bottom up & top down processing

Part 1 was all about explaining some of the factors that help to explain why perceptions can be similar or different across people. Now I'd like to turn to talking about two different perceptual processes by which the brain manages the information it receives. These two processes are referred to as bottom-up and top-down. Both are covered well in the textbook (see Section 4.7), so this information is just intended to supplement what you'll read there.

Bottom-up Processes

We most frequently use bottom-up processes when we encounter stimuli with which we have no prior experience. Given that we're essentially starting the process of perception from ground zero in these cases, 'bottom-up' means we start with the basic building blocks of the stimulus; that is, the individual features that comprise it. We then attempt to arrange these basic features in a sensible way to construct a holistic perception of what's there.

Top-down Processes

In contrast to bottom-up processing, top-down processing is used most often when we have some familiarity and experience with a stimulus. In such cases, our prior knowledge is called up from memory (more on that in the next unit!) and helps to direct our perception. That prior knowledge may be related to the specific stimulus itself, but it may also be related to the context surrounding that stimulus. As a result, the 'A,B,C/12,13,14' and 'The Cat' examples above can also be seen as examples of top-down processing. In the first case, you have called in your prior knowledge about letter and number sequences, and in the second case you're using your prior knowledge about words that start with T and end in E (or start with C and end in T).

The term 'top down', then, refers to our tendency to use that previous experience (which is kind of like a top-level executive) to organize and direct our perceptual constructions. Here's a short video to help you with the distinction between bottom-up and top-down processes. (Note: There's no sound).

Bottom-up Processes

We most frequently use bottom-up processes when we encounter stimuli with which we have no prior experience. Given that we're essentially starting the process of perception from ground zero in these cases, 'bottom-up' means we start with the basic building blocks of the stimulus; that is, the individual features that comprise it. We then attempt to arrange these basic features in a sensible way to construct a holistic perception of what's there.

Top-down Processes

In contrast to bottom-up processing, top-down processing is used most often when we have some familiarity and experience with a stimulus. In such cases, our prior knowledge is called up from memory (more on that in the next unit!) and helps to direct our perception. That prior knowledge may be related to the specific stimulus itself, but it may also be related to the context surrounding that stimulus. As a result, the 'A,B,C/12,13,14' and 'The Cat' examples above can also be seen as examples of top-down processing. In the first case, you have called in your prior knowledge about letter and number sequences, and in the second case you're using your prior knowledge about words that start with T and end in E (or start with C and end in T).

The term 'top down', then, refers to our tendency to use that previous experience (which is kind of like a top-level executive) to organize and direct our perceptual constructions. Here's a short video to help you with the distinction between bottom-up and top-down processes. (Note: There's no sound).

Combining bottom-up and top-down processes

In reality, perception of almost everything relies on both bottom-up and top-down processing going on simultaneously. Rather than thinking about perception as being 'one or the other', then, you should be taking away the idea that bottom-up processes will likely predominate when you're confronting something that's very novel and unlike almost anything you've seen before (though you will likely still be trying to find and use what limited prior knowledge your have), and when there is little in the environment (context) to assist you. In contrast, top-down processes will be more likely to occur during the perception of stimuli that are in keeping with (though maybe not identical to) things you've encountered in the past, and/or when there are cues in the environment that can help you in creating an accurate perception.

Please go back to the textbook now and read Sections 4.7 - 4.9.

The final concept map for this unit is here: