At the beginning of this unit, I had you watch the little ‘Whodunnit’ video. One of the things that video makes almost painfully clear is the fact that although it often ‘feels’ as though our senses are creating a faithful copy of the world around us, in fact the opposite is true. We miss more than we take in.

I want to foreshadow something I’ll speak more about later in this unit, and that’s the fact that there’s some danger in this state of affairs. When you think you have taken in all of the information, and you believe that your senses have represented it as a faithful copy of what you were exposed to, it can promote a level of confidence in what you think you know that’s unwarranted. It’s not uncommon for people to believe with absolute certainty that they know exactly what they saw, heard, or felt when in fact their representation may be faulty. That’s not to say that your senses constantly fail you (as I said before, they’re remarkably efficient at dealing with an avalanche of information from the world around you); I’m only saying that they’re not as perfect as you believe them to be, and that the seamless view they give you of the world may not always be a totally faithful replica of what’s actually there.

So why is it that we don’t always have an accurate record of the information in the world? How is it that you didn’t know that the painting above the fireplace had changed, that the butler had swapped his rolling pin for a candlestick, and that various plants had appeared and disappeared in that Whodunnit film clip?

There are a few reasons that help to explain our imperfect representations of the world. The one we’re going to talk about in this section relates to attention.

One of the challenges that we face in forming perfect representations of what we see, hear, taste, smell and so on is the fact that, as mighty as it is, your brain simply cannot process all of the information that you’re exposed to out there in the world – there’s just too much to take in. As a result, only some of the sensory information that’s available is sent to the brain.

Attention is the process by which we whittle down the information we’re going to prioritize; put another way, it’s the step that determines what sensory information will be sent to the brain and dealt with during the perception stage. Lots of things get left behind in this stage and are not processed by the brain. Chris Chabris, a psychologist whose work I’ll describe shortly, describes this process as ‘the brutal cage fight of attention’, but many people describe it in less aggressive terms, often referring to attention as a bottleneck. Here, then, is where the massive amount of sensory information we’re exposed to is squeezed down to something manageable that the brain can handle.

In this sense, attention is truly a limited resource – when you devote a lot of it to completing a particular task, you have significantly less available to engage in other tasks. This is why multitasking with challenging tasks isn’t really possible. Lots of people believe they’re good multitaskers – in my experience young people and women, in particular, often think they’re really good at it. But the reality is that no one is terribly good at multitasking, especially when it involves two or more difficult tasks. If you want to get a sense of what real multitasking feels like, try the task that’s outlined in this next video:

I want to foreshadow something I’ll speak more about later in this unit, and that’s the fact that there’s some danger in this state of affairs. When you think you have taken in all of the information, and you believe that your senses have represented it as a faithful copy of what you were exposed to, it can promote a level of confidence in what you think you know that’s unwarranted. It’s not uncommon for people to believe with absolute certainty that they know exactly what they saw, heard, or felt when in fact their representation may be faulty. That’s not to say that your senses constantly fail you (as I said before, they’re remarkably efficient at dealing with an avalanche of information from the world around you); I’m only saying that they’re not as perfect as you believe them to be, and that the seamless view they give you of the world may not always be a totally faithful replica of what’s actually there.

So why is it that we don’t always have an accurate record of the information in the world? How is it that you didn’t know that the painting above the fireplace had changed, that the butler had swapped his rolling pin for a candlestick, and that various plants had appeared and disappeared in that Whodunnit film clip?

There are a few reasons that help to explain our imperfect representations of the world. The one we’re going to talk about in this section relates to attention.

One of the challenges that we face in forming perfect representations of what we see, hear, taste, smell and so on is the fact that, as mighty as it is, your brain simply cannot process all of the information that you’re exposed to out there in the world – there’s just too much to take in. As a result, only some of the sensory information that’s available is sent to the brain.

Attention is the process by which we whittle down the information we’re going to prioritize; put another way, it’s the step that determines what sensory information will be sent to the brain and dealt with during the perception stage. Lots of things get left behind in this stage and are not processed by the brain. Chris Chabris, a psychologist whose work I’ll describe shortly, describes this process as ‘the brutal cage fight of attention’, but many people describe it in less aggressive terms, often referring to attention as a bottleneck. Here, then, is where the massive amount of sensory information we’re exposed to is squeezed down to something manageable that the brain can handle.

In this sense, attention is truly a limited resource – when you devote a lot of it to completing a particular task, you have significantly less available to engage in other tasks. This is why multitasking with challenging tasks isn’t really possible. Lots of people believe they’re good multitaskers – in my experience young people and women, in particular, often think they’re really good at it. But the reality is that no one is terribly good at multitasking, especially when it involves two or more difficult tasks. If you want to get a sense of what real multitasking feels like, try the task that’s outlined in this next video:

At this point you may be mentally cataloguing all the ways I’m wrong about your ability to multitask. You’ll be thinking about how you can talk on the phone with your brother while you fold your laundry, maybe, or how you can read your textbook while you make yourself a snack, or even just walk and talk at the same time. You may even have convinced yourself that you can safely talk on the phone while driving (although I really hope you haven’t). There’s a reason why those things feel possible, and why you can often do them successfully at the same time. But it’s not because you can multitask – instead, it has to do with the staggering power of your memory, and it’s something we’ll return to in the next unit. For now, let’s just agree that attention is limited and move on to talk a bit about how it gets directed toward some things and away from others.

I said earlier that we filter information from the environment and pay attention only to some things – this is the origin of the term selective attention. We 'select' what we want or what we think we’ll need and we send that to the brain for the perception step.

Talking about selective attention this way makes it seems as though somehow it’s a deliberate and thoughtful process, but that’s not true. It’s not like you consciously use S2 to think, every waking moment of every day – yes, I need to focus on this; nah, that’s not worth my time. Sometimes you may call in the processing power of S2 to do that, and consciously focus your attention on something, but a lot of the time the direction of attention is not a conscious process – you’re not at all aware of ‘deciding’ what you’re going to focus on and what you’re going to ignore. Put another way, the control of attention is typically shared by S1 and S2.

I said earlier that we filter information from the environment and pay attention only to some things – this is the origin of the term selective attention. We 'select' what we want or what we think we’ll need and we send that to the brain for the perception step.

Talking about selective attention this way makes it seems as though somehow it’s a deliberate and thoughtful process, but that’s not true. It’s not like you consciously use S2 to think, every waking moment of every day – yes, I need to focus on this; nah, that’s not worth my time. Sometimes you may call in the processing power of S2 to do that, and consciously focus your attention on something, but a lot of the time the direction of attention is not a conscious process – you’re not at all aware of ‘deciding’ what you’re going to focus on and what you’re going to ignore. Put another way, the control of attention is typically shared by S1 and S2.

factors that impact our attention

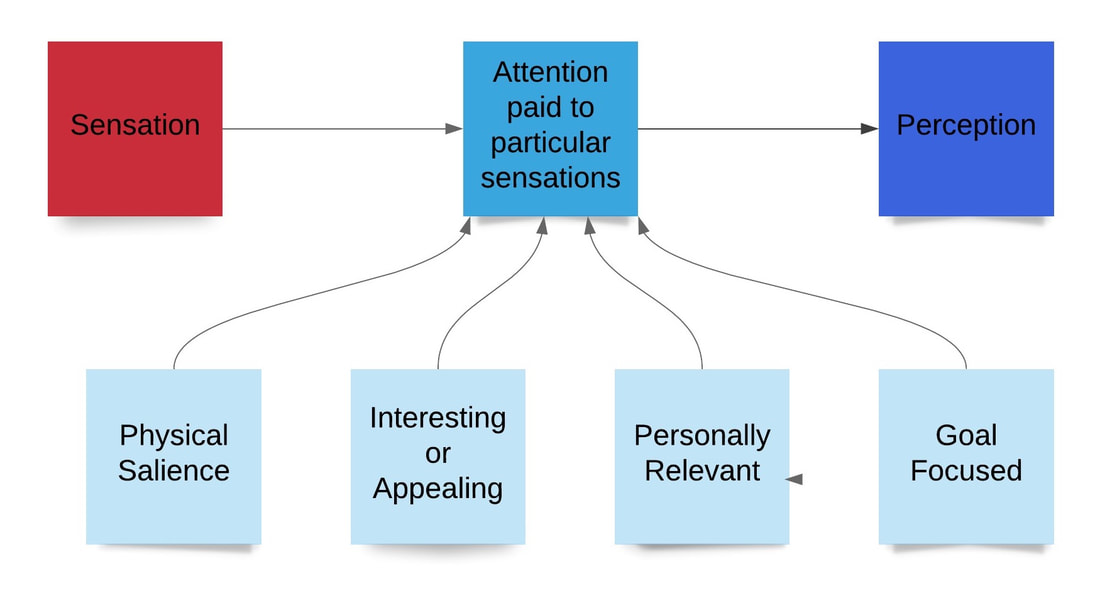

So what kinds of things determine what we pay attention to, and what we ignore? Section 4.2 outlines a few things (intensity, repetition, contrast/change), but I think that list is incomplete.

The next video will outline four of the key factors that govern our attention, drawing together some of the information that's presented in different parts of Section 4.2.

The next video will outline four of the key factors that govern our attention, drawing together some of the information that's presented in different parts of Section 4.2.

So what the Yarbus study tells us is that sometimes we miss information because our attention is directed elsewhere. And while physical salience, interest and attractiveness, and personal relevance can all impact attention, that study showed us how goals have a powerful effect on our attentional focus.

If we’re connecting this idea back to sensation, then what the Yarbus study tells us is that sometimes sensory information is not sent to the brain for processing simply because it was never really picked up by the transducers in the first place.

You’ve probably seen evidence of how selective attention results in information not making it to the brain, and consequently not being perceived. Here are some examples from everyday life. Spoiler: The last one includes graphic and unsettling evidence of how multitasking can result in traffic accidents - don't watch it if you feel that it might be upsetting to you.

Now at this point, I wouldn’t be surprised if you were thinking that all of this seems a bit obvious. If you’re not paying attention to something – in this case, not looking at it because it doesn’t fit in with your goals in that moment – then it’s pretty clear that the brain won’t perceive it (that is, you won’t see it).

So let’s take things one step further now. Please take a look at this video:

You may have been surprised at the outcome of that video.

How do such things happen? In this next video, I'll try to explain (with a little help from my son Callum, who's waited a long time to provide his message to 1500 of my students).

What you saw going on in the Monkey Business Illusion is related to inattentional blindness – it’s a phenomenon called change blindness. While inattentional blindness is about failing to notice specific aspects of a scene, change blindness refers to an inability to detect gradual changes in a scene. Change blindness is at the heart of the surprise ending in the Whodunnit video, which you saw at the very beginning of this unit.

We'll finish up this section by taking the concept of attention outside of the laboratory and into the real world. In this regard, the textbook provides some examples of how research on attention is relevant in the courtroom (see Section 4.10). To see how it relates to medical contexts, take a look at this next video.

At this point, you should go back to the text and read Sections 4.2 and 4.10.

In terms of our concept map, here's where we're up to:

In terms of our concept map, here's where we're up to: